The Gettysburg Address as a Powerpoint

On the 150th anniversary of the speech, let's consider how the corporate world's native medium might improve it.

When powerful, executive politicians speak, they often forgo visual aids. Obama, Reagan, Kennedy: There’s something about the prestige of the president, of presiding, that demands he (or she) face the nation straight-on and honestly, with... his face.

But what if that wasn’t the case? Thirteen years ago, Peter Norvig, the current director of research at Google, suffered a dark night of the soul. Powerpoint presentations, he felt, ruled everything around him. Sales pitches, mission statements, even (shudder) inspirational speeches: All had been processed and extruded by the harsh, homogenizing gizzard of Microsoft’s leviathan.

So, he wondered, what if the Powerpoint had existed earlier in history? What if Lincoln, for example, had turned to the software in a time of utmost national need—what if, oh my gosh, what if Lincoln had delivered the Gettysburg address as a Powerpoint?

And so the stuff of Internet myth came to be.

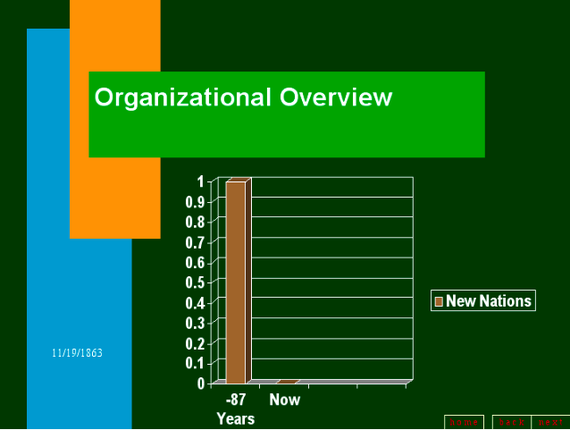

In Norvig’s hands, the near-biblical phrase—“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”—becomes (what else?) a chart:

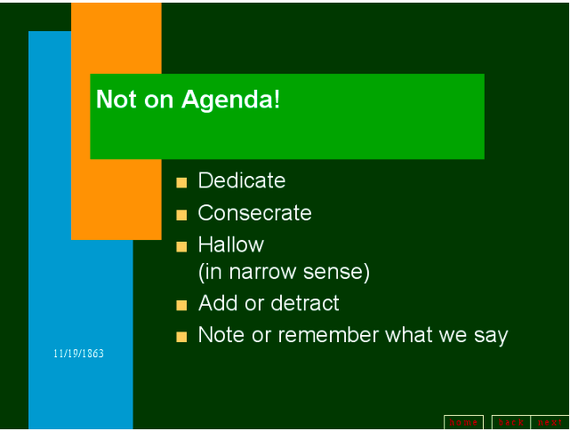

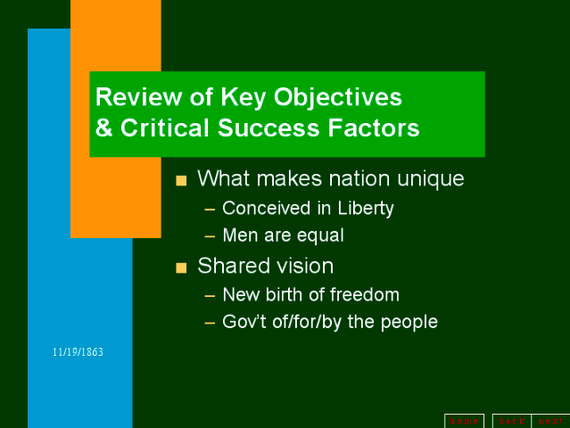

The speech remains concise, though. Norvig prunes Lincoln’s famous 268 words to only six slides. The president’s cascading phrases concerning what, “in a larger sense,” can and cannot be done are converted into a series of bullet points:

And, in a coup de grâce, Norvig compresses two of the most ringing phrases of Lincoln’s oration into a single slide. Before Powerpoint, who realized that a few words could be edited out of “All men are created equal,” or that “of the people, by the people, for the people” was best expressed with slashes?

Since posting the deck 13 years ago, Norvig has seen a new birth of traffic himself; his now-classic creation has appeared in the Guardian, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal. Edward Tufte, probably the world’s most famous information designer, called it “the trump card of subversive and ironic PP productions.” By 2007, over 1.6 million visitors had seen Norvig’s humble Powerpoint.

In a making-of page on his site, Norvig explains how the hideous genius came to be. Turns out, he only enabled by the beast known as Autocontent Wizard:

[When I thought of the idea,] I thought I'd be in for a late night doing some serious research: in color science to find a truely garish color scheme; in typography to find the worst fonts; and in overall design to find a really bad layout. But fortunately for me, the labor-saving Autocontent Wizard took care of all this for me! It suggested a red-on-dark-color choice for the navigation buttons that makes them very hard to see; it chose a serif font for the date that is illegible in low-resolution web mode, and of course Excel outdid itself on the graph, volunteering the 0.1 to 0.9 between the 0 and 1 new nations. All I had to do was take Lincoln's words and break them into pieces, making sure that I captured the main phrases of the original, while losing all the flow, eloquence, and impact.

And so he did, to which we say, bravo. But even since Norvig lowered the peak of American political speech, the cost of making charts has come down. The president may not fire up the ol’ digital projector soon, but—even in “the world’s greatest deliberative body”—its analog equivalent is out in full-force.

Who can forget Senator Tom Coburn’s peroration on the nature of democracy?

Or, in the lesser house, Congresswoman Jackie Speier’s indelible hashtag?

Or, finally, this treatise on the nature of economics?

Floorcharts.com documents the rest of the madness.

I wonder: With chart-centric policy writing as popular as it is now, how long until our executive-in-chief strolls across the Oval Office, warmly declaiming, “Let me show you a histogram…”